I want to consider the meaning of the term “justice,” which in common usage implies “to render to every man his due,” according to the famous expression of Ulpian, a Roman jurist of the third century. In reality, however, this classical definition does not specify what “due” is to be rendered to each person. What man needs most cannot be guaranteed to him by law. In order to live life to the full, something more intimate is necessary that can be granted only as a gift: we could say that man lives by that love which only God can communicate since He created the human person in His image and likeness. Material goods are certainly useful and required – indeed Jesus Himself was concerned to heal the sick, feed the crowds that followed Him and surely condemns the indifference that even today forces hundreds of millions into death through lack of food, water and medicine – yet “distributive” justice does not render to the human being the totality of his “due.” Just as man needs bread, so does man have even more need of God. Saint Augustine notes: if “justice is that virtue which gives every one his due ... where, then, is the justice of man, when he deserts the true God?” (De civitate Dei, XIX, 21).

Friday, 19 February 2010

A Greater Justice

After reflecting last time on Plato's study of justice in The Republic, it seems appropriate to refer now to Pope Benedict's reflections on justice, which form his message for the beginning of Lent 2010. There he begins:

Wednesday, 10 February 2010

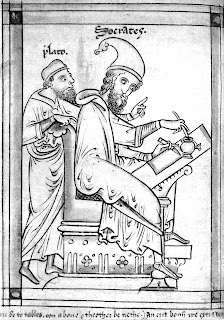

Plato's Republic

I tend to write from within the Christian Platonist tradition. Plato himself, however, I have never studied as deeply as I would have liked. The Republic I have read mainly for its teachings on epistemology and education, but I still do not quite know how to take the whole political discussion, in which Socrates seems to advocate that wives and children should be held in common - in other words, he proposes the destruction of the family for the sake of good government. Christians sympathetic to Plato's other views tend to shy away from this rather central theme in The Republic, and focus more on the very different prescriptions and arguments in his later dialogue, The Laws. So was Plato a totalitarian or communist thinker, as Karl Popper and others have alleged? Or is there some

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)